Escaping the magics of the frameworks: 5. The framework

The last magical framework feature I want to get rid of is the Spring Boot framework itself.

is not the only choice available.

I also have the choice of which framework to use that does not blind me with all its glowing magic.

In this series of articles I replaced, magic by magic, some framework’s features until I had no more sorceries to wield. I’ve done it in baby steps, explaining the reasons why, and keeping my application working all the time.

You can read about frameworks, what’s wrong with magics, configuration as code, explicit routing and test decoupling in the previous articles. I also addressed how to deal with the dependencies in a more explicit way.

From now on I will continue where I left off with the code examples tackling the replacing of the Spring Boot framework.

Please this article on LinkedIn and tag me if you want to start a public conversation on this topic or contact me if you prefer to talk about it privately.

The framework dilemma

Generally I don’t like the way some frameworks do magic tricks (generally annotation stuff) that make us inconscious about what’s going on.

But we choose a full-blown framework because we don’t want to think about things that have already been solved thousands of times. In that way we get everything we need “magically” and this is really tempting.

Think about it for a moment. This comes with a cost. The cost of flexibility, code navigation and understanding.

But the framework choice is not ON-OFF

There are many choices available that go from a full-control approach to the no-control approach. Below some examples:

- I write everything on my own. I reinvent the wheel every time wasting a lot of time, risking to introduce nasty bugs

- I write my own application, but I use some libraries that help me to handle some already solved problems

- I use a micro-framework only to solve a few related problems. For everything else I use some libraries that help me to handle some other common stuff

- I use a full-blown framework, that does almost everything for me, I don’t need to think, I only have to care about putting some code inside it hoping that my needs never diverge from the framework usecase

That choice depends on many factors like the team, the business context, the technologies used and so on. Anyway I usually prefer to deliberately choose and compose the libraries I need to solve specific usecases and I try to find libraries that do not introduce too much magic.

In a web-service context, for example, I usually adopt a micro-framework that abstract only the web-server part, and it does it very well. Then I add the libraries I need only when I need them, like the Http client or a library to communicate with the database (see Why I avoid ORMs).

Switch the framework

In my application example not using a framework at all it’s like reinventing the wheel. For this reason I want to replace the Spring Boot framework with a less magical one.

In the Kotlin context there are quite a few less magical frameworks I could have used like Ktor or http4k. I chose Javalin for its first class interoperability between Java and Kotlin, and for their claim against magic that you can find in their repository:

Javalin is more of a library than a framework. Some key points:

- You don’t need to extend anything

- There are no @Annotations

- There is no reflection

- There is no other magic; just code.

Currently I have a situation where I’m dependent on the framework with only two classes: Application and GreetingController.

First of all I need to change the dependencies declared in the build.gradle file. I need to:

- Remove

kotlin-reflectsince I no longer use reflection - Replace

spring-boot-starter-webwithjavalinfor http server,jackson-databindfor Json parsing andslf4j-simplefor logging. - Replace

spring-boot-starter-testwithjunit-jupiter - Keep

topinamburandjson-unit-assertjthat simplify http requests and test assertions

(See the build.gradle diff - tag 21-FRAMEWORK).

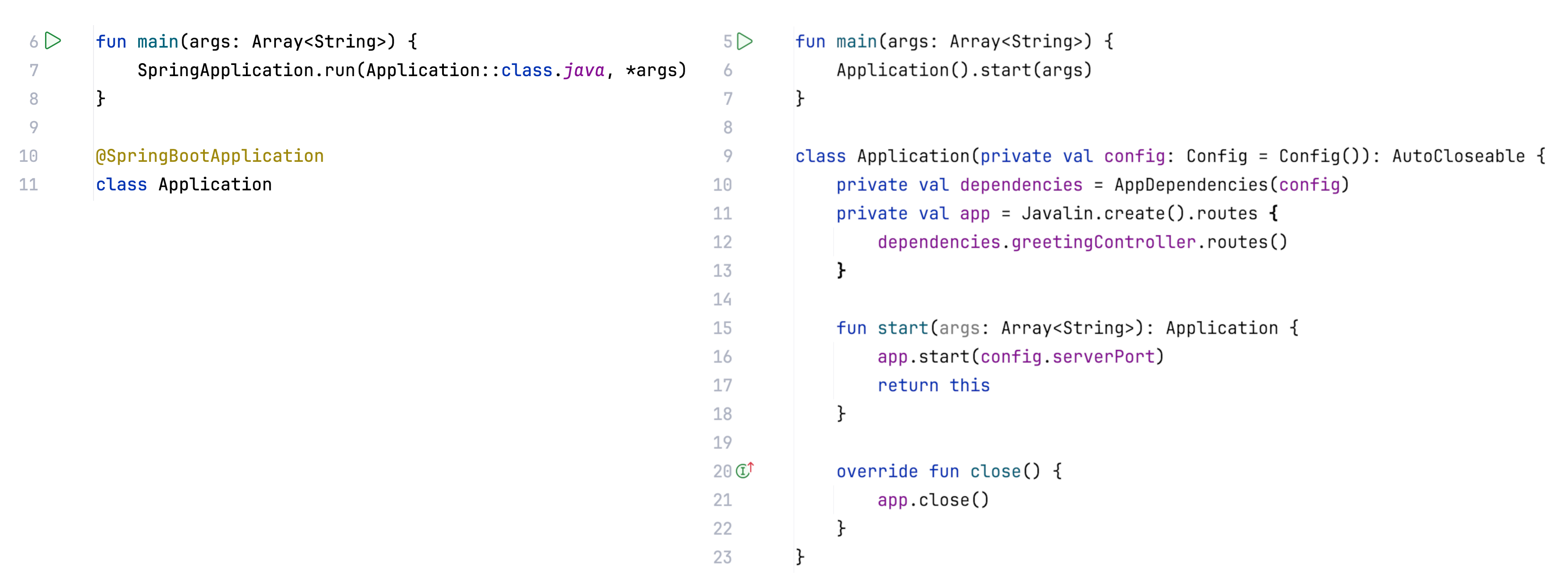

Now it’s the turn of the Application class.

Application class

I have an Application class that handles the @SpringBootApplication annotation and configures the server port as a default property. Then I need to instantiate a Router Bean, that will be evaluated at runtime, in which to put all the routes.

with spring boot

@SpringBootApplication

class Application(private val config: Config = Config()): AutoCloseable {

private val dependencies = AppDependencies(config)

private var appContext: ConfigurableApplicationContext? = null

private val app = SpringApplication(Application::class.java).apply {

setDefaultProperties(mapOf("server.port" to config.serverPort))

addInitializers(beans {

bean {

router {

dependencies.greetingController.routes(this)

}

}

})

}

fun start(args: Array<String>): Application {

appContext = app.run(*args)

return this

}

override fun close() {

appContext?.close()

}

}

Using Javalin the Application class becomes a lot easier and straightforward. During the creation of the Javalin application I programmatically set the routes I want to use.

with javalin

class Application(private val config: Config = Config()): AutoCloseable {

private val dependencies = AppDependencies(config)

private val app = Javalin.create().routes {

dependencies.greetingController.routes()

}

fun start(args: Array<String>): Application {

app.start(config.serverPort)

return this

}

override fun close() {

app.close()

}

}

(See the Application diff - tag 21-FRAMEWORK)

I usually avoid AppDependencies class at the beginning and I instantiate the controllers directly in the Application class.

In the example I extracted the dependencies creation logic only to highlight the similarities with the Spring Boot classes annotated with @Configuration where I can also define dependencies.

For example, if I had not used AppDependencies class, the Application code would have become something like this:

class Application(private val config: Config = Config()) : AutoCloseable {

private val counterService = CounterService(config.exampleInitial)

private val app = Javalin.create().routes {

GreetingController(counterService).routes()

}

// [...]

}

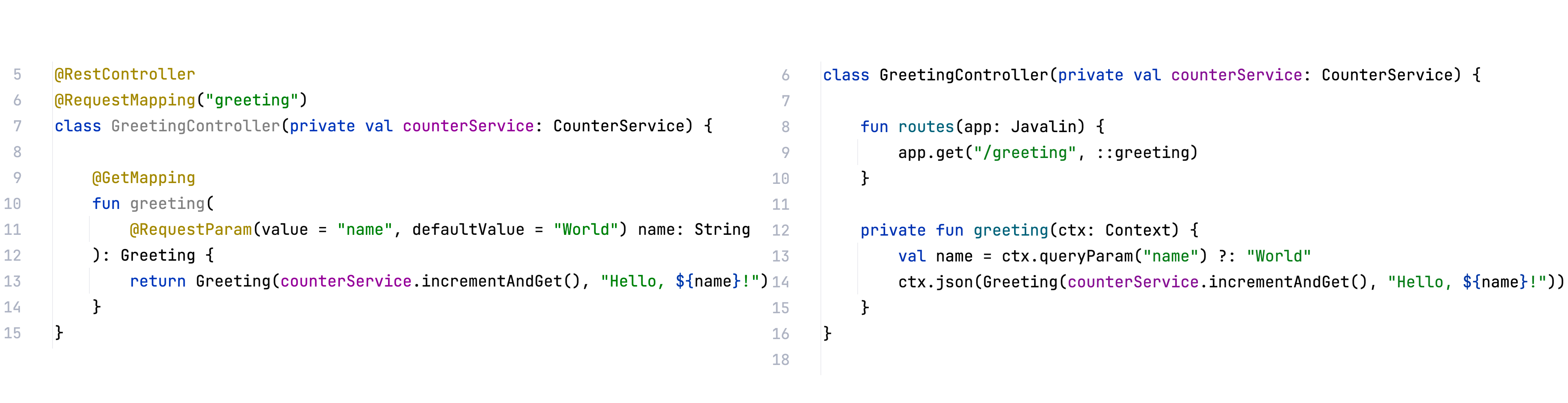

GreetingController class

The controller looks very similar, there are only few changes in the syntax, but the concept is the same.

with spring boot

package com.example

import org.springframework.web.servlet.function.RouterFunctionDsl

import org.springframework.web.servlet.function.ServerRequest

import org.springframework.web.servlet.function.ServerResponse

import org.springframework.web.servlet.function.ServerResponse.ok

class GreetingController(private val counterService: CounterService) {

fun routes(router: RouterFunctionDsl) {

router.GET("/greeting", ::greeting)

}

private fun greeting(request: ServerRequest): ServerResponse {

val name = request.param("name").orElse("World")

return ok().body(Greeting(counterService.incrementAndGet(), "Hello, ${name}!"))

}

}

with javalin

package com.example

import io.javalin.apibuilder.ApiBuilder.get

import io.javalin.http.Context

class GreetingController(private val counterService: CounterService) {

fun routes() {

get("/greeting", ::greeting)

}

private fun greeting(ctx: Context) {

val name = ctx.queryParam("name") ?: "World"

ctx.json(Greeting(counterService.incrementAndGet(), "Hello, ${name}!"))

}

}

I slightly prefer the request -> response function above, but I will never see it in a real Spring Boot project. Besides, the javalin route is slightly more explicit about the format of the response body, because I use the Context::json method.

(See the GreetingController diff - tag 21-FRAMEWORK)

Expose the magic

I’m at the end of this magical journey. It’s time for me to see how far I have come.

So I want to compare the starting setup (Spring Boot, on the left) with the current one (Javalin on the right).

It’s time to expose the framework magic!

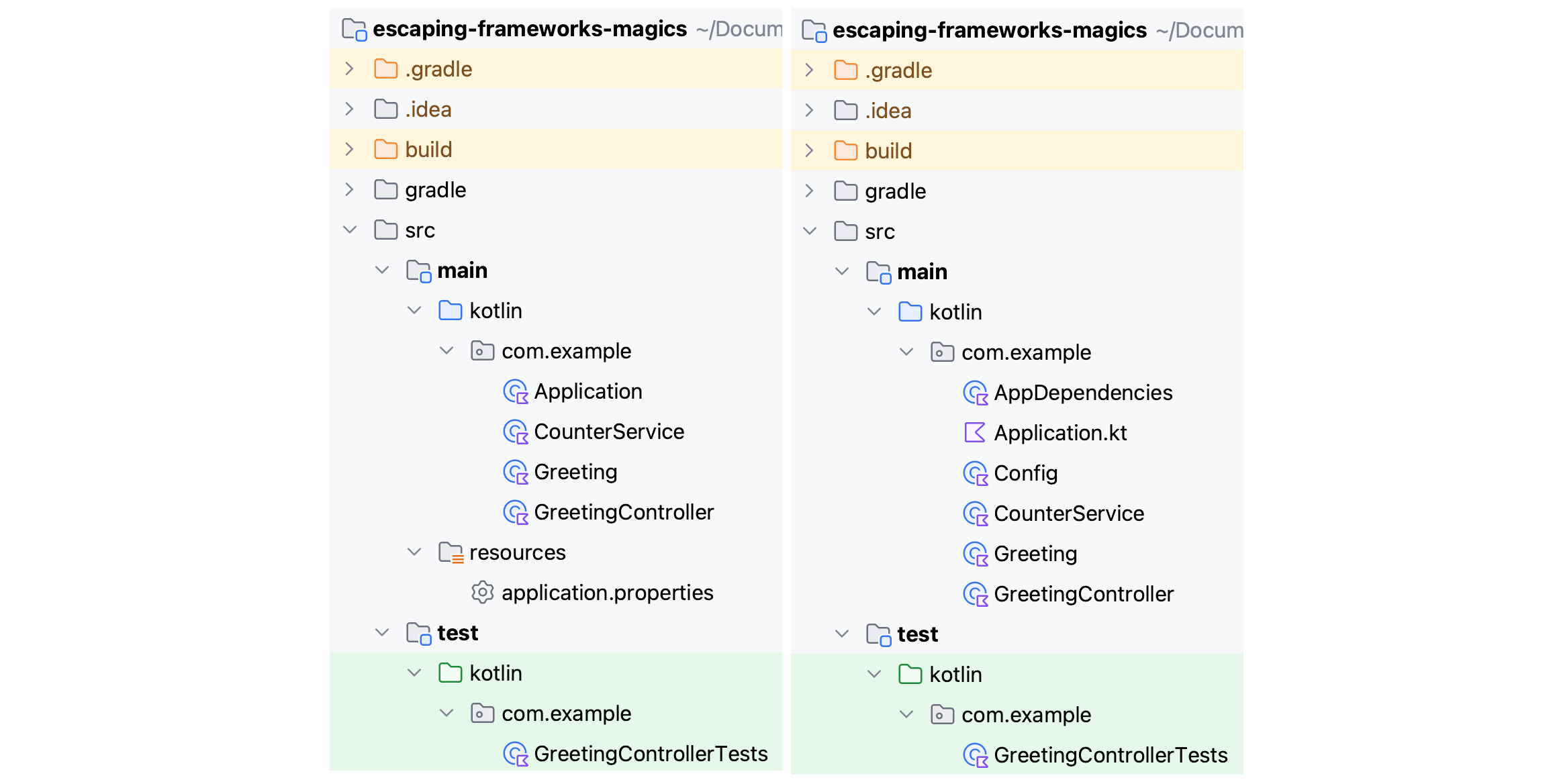

Project structure

The application.properties become Config.kt, and the new AppDependencies.kt can be avoided by declaring the controllers directly inside the Application class.

Let’s say the project structure is almost identical, but everything is a kotlin file.

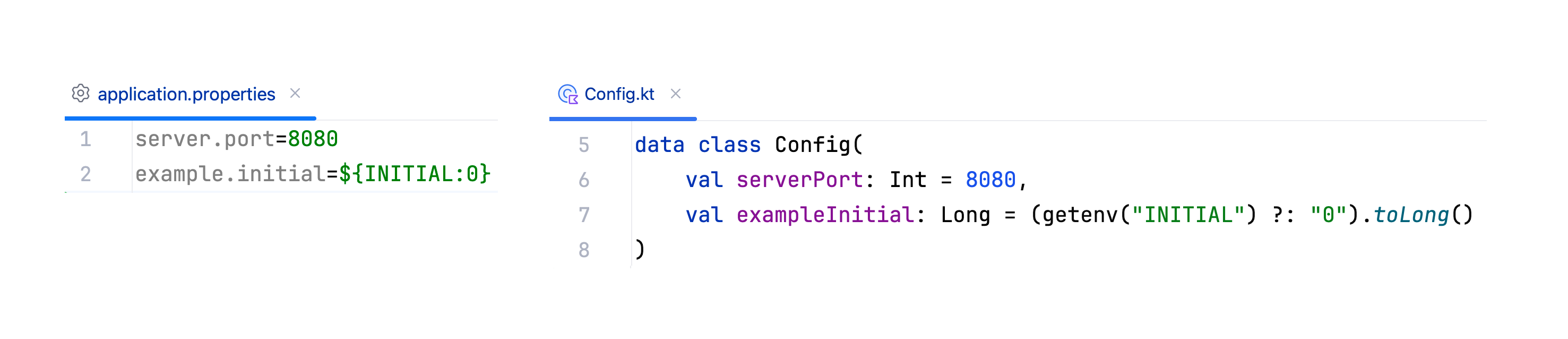

Configuration

Now I leverage on the compiler to check the usages of each property and I can use different types in addition to string. Through the env variables the configuration values can still be overwritten in different environments like production or staging. Besides I can explicitly inject my Config implementation into the application for tests.

(read more here: Escaping the magics of the frameworks: 1. Configuration)

Application

Here I need to explicitly write down the routes. In this way, when I’m lost, I can always start from the application entrypoint and navigate down until I reach the point I need.

Controller

Both have 10 lines of code. Every annotation is translated almost one to one in code. Using code has the same expressiveness plus it can be easily read, understood, tested and debugged.

(read more here: Escaping the magics of the frameworks: 2. HTTP Routing)

Tests

Now I have api tests that are a bit faster compared to the Spring Boot initial setup that uses MockMvc.

- 442ms –> Spring Boot with

MockMvc - 288ms –> Javalin app started and closed at every test

Apparently MockMvc (the way promoted by Spring Boot to test) is a bit slow compared to the Javalin start and stop, even if it’s only a Mock and not a real application startup.

(read more here: Escaping the magics of the frameworks: 3. Tests)

Dependencies

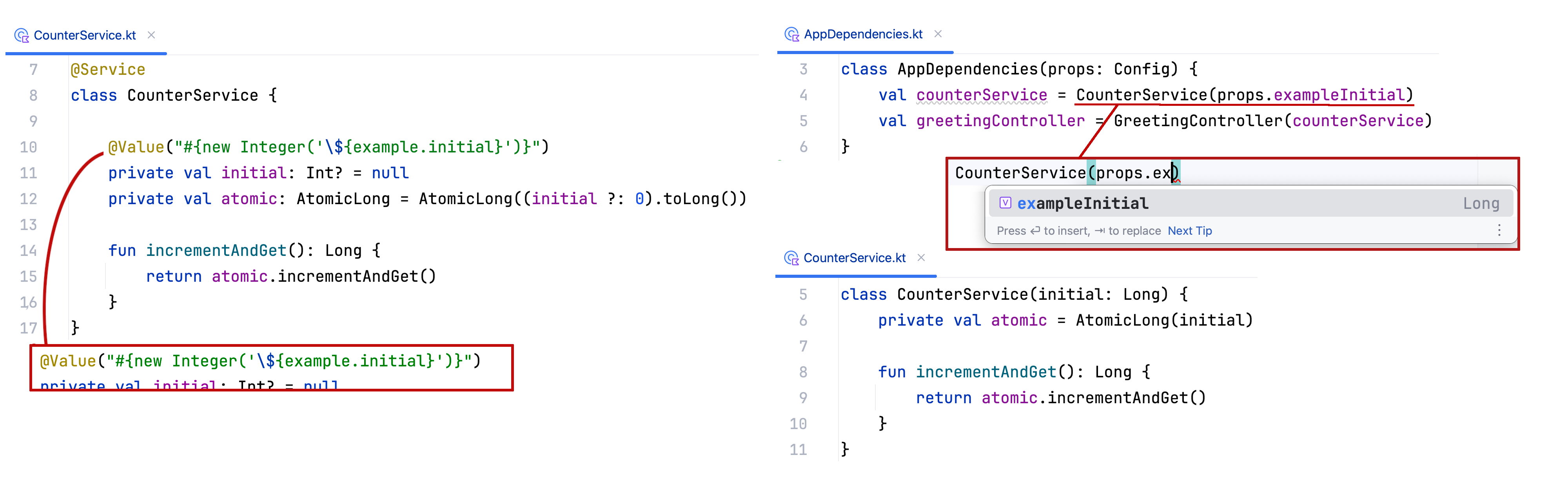

I moved out of the service all the framework details so that the service is a simple class with its injectable dependency.

(read more here: Escaping the magics of the frameworks: 4. Dependencies)

Conclusions

The structure of the project is almost identical, even the amount of code is practically the same… so what has changed?

The first big change is about who’s in control. The framework is not in control anymore. I have the control over what to use and what not to use, over what to avoid and what to adopt.

The other big change is the magic of the framework being replaced by explicit code enhancing the developer experience.

The important thing to note is that to achieve this I don’t have to reinvent the wheel every time or write my own framework. I can also resort to libraries or micro-frameworks that do a single thing very well and use them in my application.

What’s next?

Now it’s up to you. Think that sometimes we choose a framework to do things that can be done just fine (if not better) without the help of its magic tricks.

So pay attention. It’s up to you which framework to choose, if to use a set of libraries, a micro-framework or a full-blown framework.

If others have already chosen a full-blown framework years before it’s ok. You can always work towards reducing the spread of those magics making the code more explicit and gradually gaining more control over your application.

Please let me know your opinion

this article on LinkedIn and tag me if you find it interesting.